For more information: Recommended Links | Frequently Asked Questions

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Ray Brown. All rights reserved.

“First rate analysis at a cut-rate price.”

— Creative Screenwriting

Script Format: Slug Lines

A slug line is different from a scene heading. Slug lines direct our attention to what's important within a scene. They add punch, and can be used to heighten the pacing. That being said, they can become annoying if used excessively. Camera angles written as slug lines, such as “REVERSE SHOT,” are usually superfluous. Even close-ups are to be avoided, unless they reveal some detail that is vital to the story.

Slug lines cannot be used to change the setting or the time of day. It’s possible to bridge a small gap in time within a scene through the use of a slug line, but it must focus on some character or detail. As discussed in the section on scene headings, it’s not enough to simply write “LATER.”

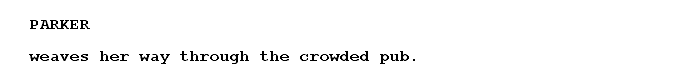

Written in ALL CAPS, the slug line may consist of just the character or characters we see in the shot:

This actually reads better than writing it as a camera direction, such as “ANGLE ON PARKER.”

Each slug line is its own element. Action or description cannot appear next to it on the same line, but must follow the slug line in a new paragraph.

While scene headings usually have two blank lines above them, slug lines always have just one.

If we wish to cut to a character named Ned in the bleachers of a football game, for example, we’d insert “NED” (without the quotes) as a shot element or slug line. In this particular instance, it would also be acceptable to break the sequence into separate scenes, using “BLEACHERS” in the scene heading.

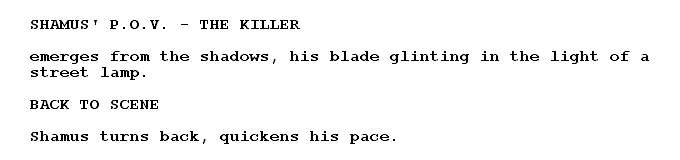

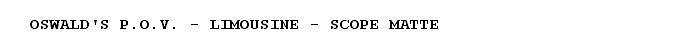

When a shot originates from a particular character’s point-of-view, it’s customary to break it out with its own slug line. This slug line must state the character by name and refer to what the character sees. It’s not enough to simply write “SHAMUS’ P.O.V.,” for example (using periods because it’s an abbreviation), without also specifying in the slug line what Shamus sees:

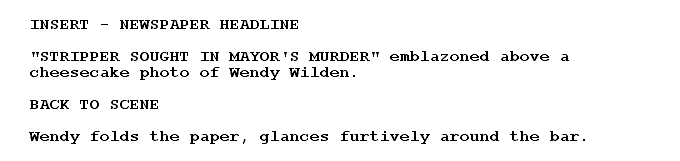

After describing the insert, we again return to the scene by means of the slug line “BACK TO SCENE.”

The use of split screen (often designated by means of a slug line) should be left to the discretion of the director. A split screen in a script often just leads to confusion, especially when the slug lines refer to left or right screen instead of a setting.

After describing a p.o.v. shot, we usually return to the scene (to get the character’s reaction) by means of the slug line “BACK TO SCENE.”

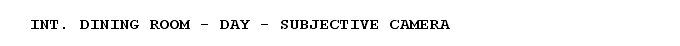

If an entire scene is viewed from a particular character’s perspective, this can be indicated by means of a separate scene heading appended with the modifier “SUBJECTIVE CAMERA”:

Point-of-view shots and subjective camera shots are usually reserved only for principal characters, as they tend to generate empathy.

If the point-of-view is through a camera viewfinder, a telescope, or a set of binoculars, it’s usually processed in post-production with an overlay. This should be designated by means of a matte:

One type of slug line is an insert, a detail shot in which no recognizable actor appears. As with all slug lines, an insert is written in ALL CAPS. It must also reference the detail within the slug line:

Next: Description

Next: Description

| Development Notes |

| Oral Consultation |

| Studio-style Coverage |

| Selling Synopsis |

| Proofreading |

| Sample Script Analysis |

| Sample Coverage |

| Sample Selling Synopsis |

| SolPix Interview |

| Creative Screenwriting Interview |

| Scriptwriter Interview #1 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #2 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #3 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #4 |

| Elements of a Great Script |

| Margin Settings |

| Scene Headings |

| Slug Lines |

| Description |

| Character Cues |

| Dialogue |

| Personal Direction |

| Transitions |

| Flashbacks |

| Montages |

| Telephone Calls |

| Registration |

| Software |