For more information: Recommended Links | Frequently Asked Questions

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Ray Brown. All rights reserved.

“First rate analysis at a cut-rate price.”

— Creative Screenwriting

Script Format: Description

A well-written script creates in the mind of the reader the experience of watching a movie. To that end, you must describe images, sounds, actions, and speech in such a way that the scenes unspool as they would on a screen.

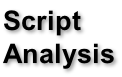

In the movies, unlike in a novel, we are limited to the physical senses of sight and sound. Refrain from describing what would not be visible or audible to us as we’re watching the movie. For example, don’t describe a character in terms of their occupation, as this usually isn’t evident from their appearance. Employ props and clothing to give us visual clues, or reveal a character’s identity subtly in dialogue.

Before you tell us what takes place, it’s a good idea to set the stage. The first time we see a particular setting, describe it briefly. Insert a blank line to separate this description from the action that follows.

Make the description kinetic and visual, but succinct and specific. Replace passive verbs (e.g. “is”) with active verbs to make the action more dynamic. Don’t editorialize by using adjectives or adverbs that express a personal reaction, such as “hideous,” “amazing,” or “incredible.”

Strip your description of any clichés and generic phrases that contribute nothing to our understanding of the characters or situation. Don’t just write that a character is standing in a room, for example, or sitting at a desk. Give them some business that indicates their personality or attitude. Open each scene with them already engaged in some action that relates to the story.

Such directions as “PAN TO,” “DOLLY IN,” and “CRANE UP” should be used sparingly. No director wants the writer to tell him how to move the camera. It’s possible to convey the shot you envision simply by describing the scene in a manner that leads the mind’s eye of the reader.

It’s not necessary to describe minor gestures and reactions. Nor is it necessary to slug out a different camera angle (e.g. “BACK TO JONATHAN”). Such overwritten description tends to distract rather than enhance, especially when it interrupts an exchange of dialogue. Leave it to the actors and the director to interpret the lines and block out the scene.

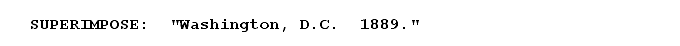

Do not abbreviate “SUPERIMPOSE” as “SUPER.” Do not place the legend above the scene heading or immediately below the scene heading, but within the scene itself. In other words, it should come after at least one sentence of description. The term “TITLE:” would be incorrect. Titles appear only at the beginning of a movie. The term “TITLE CARD:” designates a separate graphic element, a card that is not superimposed over the scene. Title cards were common in silent films, but are seldom used today.

In action and description, a character’s name should be written in ALL CAPS only when that character first appears in the script. After that, the name should appear in Title Case. This holds true even for bit parts, such as Medical Examiner.

Always employ the number symbol (#) when referring to numbered characters, such as Girl #1 and Girl #2.

A character’s age should be written as numerals, set off by commas, not enclosed in parentheses.

Be consistent in naming your characters. If you introduce an Armed Man, for example, always call him the Armed Man. Don’t call him Thug for the sake of variety. That can be confusing.

To minimize any possibility of confusion (and to make the script easier to read), avoid naming two principal characters with the same initial letter (e.g. Albert and Anderson).

Refrain from using ALL CAPS just for emphasis. There are just three situations when it’s permissible to use ALL CAPS in description: 1) when introducing a character, 2) to denote camera direction, and 3) to draw attention to sound effects. The main reason for using ALL CAPS is to aid the production manager in breaking down the script.

When indicating a sound effect, only one word should appear in ALL CAPS. For example, you might write “the SOUND of silverware hitting the floor” or “the sound of silverware HITTING the floor.”

When wrapping lines, do not insert hyphens to break words.

Do not justify the margins. A fully justified script may appear neater, but it’s more difficult to read than a script with paragraphs that are “ragged right.”

There is no need to lead into some dialogue by describing that a particular character says something, as this purpose is served by the character cue.

If possible, refrain from interrupting a passage of dialogue with tiny bits of direction written as description. Such direction, if necessary, would be more economically presented as a parenthetical.

An ellipsis consists of three periods. No more, no less. There should be a space between an ellipsis and the text that follows it, but no leading space. An ellipsis does not have any spaces between the periods. Make sure you’re not using an ellipsis symbol (usually the result of writing in Microsoft® Word® with its “AutoCorrect” feature), as this symbol places the periods too close together for a screenplay.

Text that is visible onscreen, such as a newspaper headline, words on a sign or on a computer monitor, should be set off in quotes.

Song titles in description should also be enclosed in quotes.

The titles of books and publications should be underscored when they appear in description.

If an action element describes something that occurs off-screen, then the term “off-screen” should be abbreviated as “o.s.”

The abbreviations for background (b.g.) and foreground (f.g.) are written in lower case. The same applies to the abbreviation for point-of-view (p.o.v.), without sound (m.o.s.), voice-over (v.o.), and off-screen (o.s.) when used in description.

It’s not necessary in the body of a scene to inform us as to the setting, the time of day, or whether it’s an interior or exterior, as this is already known from the scene heading.

If a legend, such as a locale or a date, is to be superimposed upon a scene, then standard format dictates it be placed within quotes and preceded by the word “SUPERIMPOSE:” (in ALL CAPS with a colon):

Next: Character Cues

Next: Character Cues

| Development Notes |

| Oral Consultation |

| Studio-style Coverage |

| Selling Synopsis |

| Proofreading |

| Sample Script Analysis |

| Sample Coverage |

| Sample Selling Synopsis |

| SolPix Interview |

| Creative Screenwriting Interview |

| Scriptwriter Interview #1 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #2 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #3 |

| Scriptwriter Interview #4 |

| Elements of a Great Script |

| Margin Settings |

| Scene Headings |

| Slug Lines |

| Description |

| Character Cues |

| Dialogue |

| Personal Direction |

| Transitions |

| Flashbacks |

| Montages |

| Telephone Calls |

| Registration |

| Software |